Parker Solar Probe Mission Turns a Terrific Two

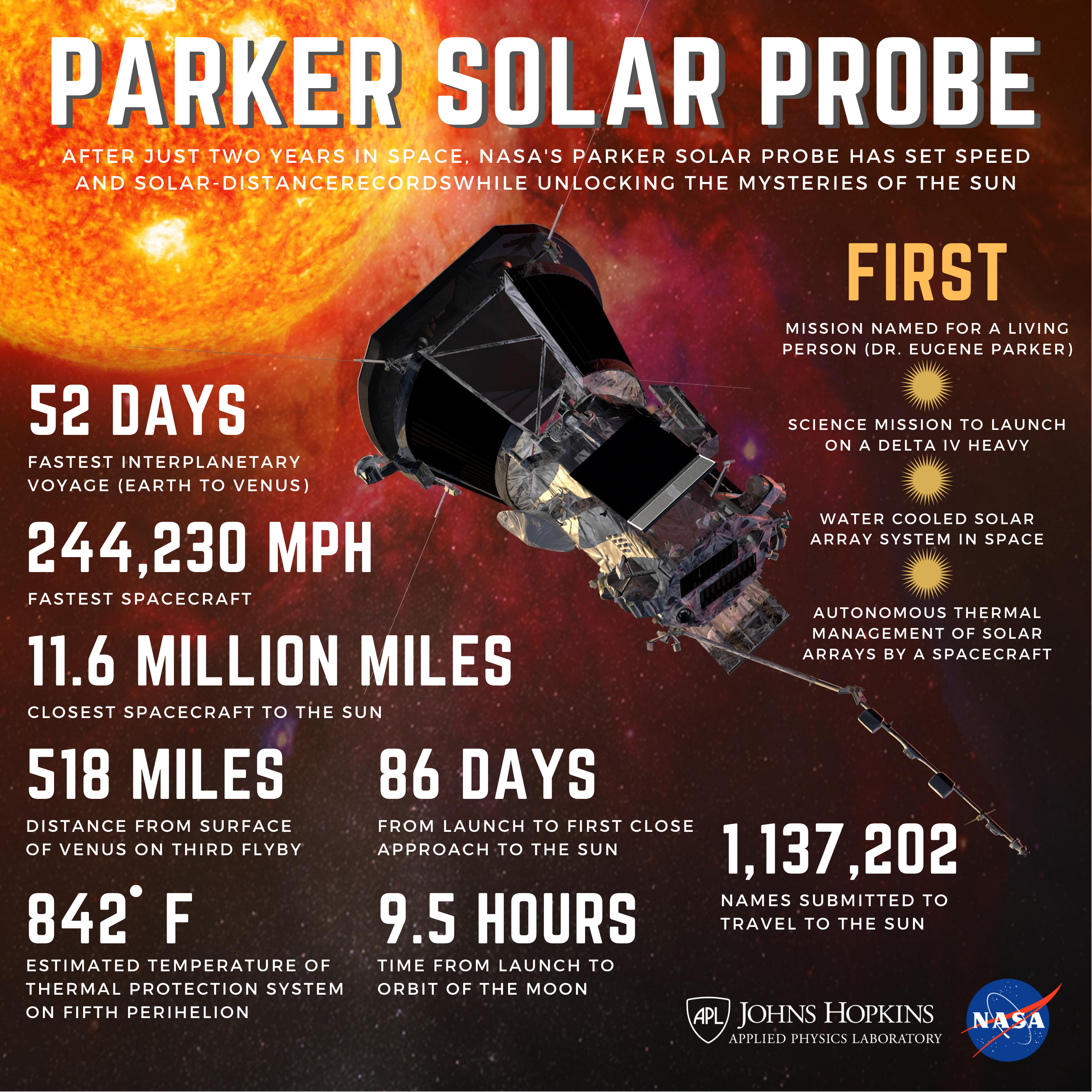

Posted on 2020-08-12 10:52:36Perched atop a powerful Delta IV Heavy rocket, NASA's Parker Solar Probe roared into the predawn skies over Florida's Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on Aug. 12, 2018. The durable spacecraft, built and operated at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, has already set speed and solar-distance records, and continues on its journey to unlock the mysteries of our star. We mark the second launch anniversary with a look back at the discoveries and milestones reached during Parker Solar Probe's most recent year in space.

Shining New Light on the Sun

The Parker Solar Probe mission returned unprecedented data from near the Sun, culminating in several discoveries published in the journal Nature on Dec. 4, 2019. Among the findings were new ideas on how the Sun's constant outflow of material, the solar wind, behaves. Seen near Earth — where it can interact with our planet's natural magnetic field and cause space weather effects that interfere with technology — the solar wind appears to be a relatively uniform flow of plasma. But Parker Solar Probe's observations revealed a complicated, active system not seen from Earth.

The Solar Wind's First Whispers?

Scientists have studied the solar wind for more than 60 years, but they're still puzzled over some of its behavior. While they know it comes from the Sun's million-degree upper atmosphere called the corona, the solar wind, for example, doesn't slow down as it leaves the Sun — it speeds up, and it has a sort of internal heater that keeps it from cooling as it zips through space. Yet through the wind's roar, NASA's Parker Solar Probe heard the small chirps, squeaks and rustles that hint at the origin of this mysterious and ever-present wind. In January, scientists got to hear these sounds for the first time.

'We are looking at the young solar wind, being born around the Sun," said Nour Raouafi, Parker Solar Probe project scientist of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. "And it's completely different from what we see here near Earth."

Speed, Distance Records Fall on Fourth Close Pass

At 4:37:42 a.m. EST on Jan. 29, Parker Solar Probe broke speed and distance records as it completed its fourth close approach of the Sun. The spacecraft traveled 11.6 million miles from the Sun's surface at perihelion, reaching a speed of 244,226 miles per hour. Those marks toppled Parker Solar Probe's own records for closest spacecraft to the Sun — about 15 million miles from the surface — and fastest human-made object, which had been 213,242 miles per hour.

Longest Science Observation Campaign Begins

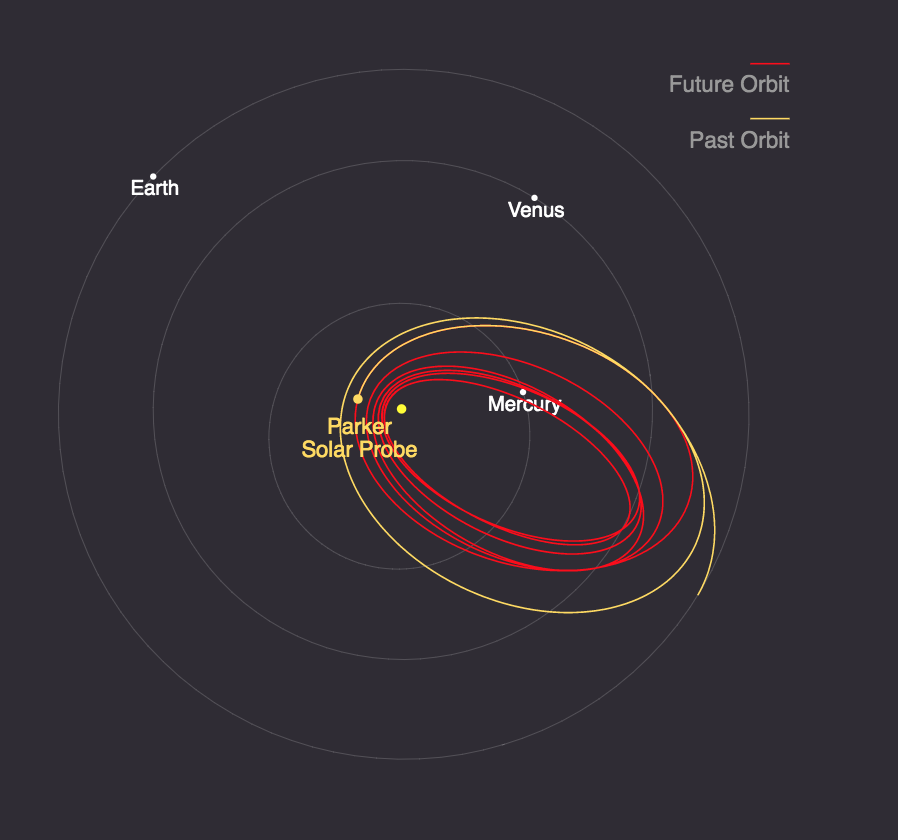

On May 9, Parker Solar Probe began its longest observation campaign to date. The spacecraft, which had already completed four progressively closer orbits around the Sun, activated its instruments while 62.5 million miles from the Sun's surface -- some 39 million miles farther out than during a typical solar encounter. The four instrument suites continued to collect data through June 28, markedly longer than the mission's standard 11-day encounters.

The nearly two-month campaign was spurred by Parker Solar Probe's earlier observations, which revealed significant rotation of the solar wind and solar wind phenomena occurring much farther from the Sun than scientists previously thought. The earlier activation of the science instruments allowed the team additional space to trace the evolution of the solar wind as it speeds away from the Sun.

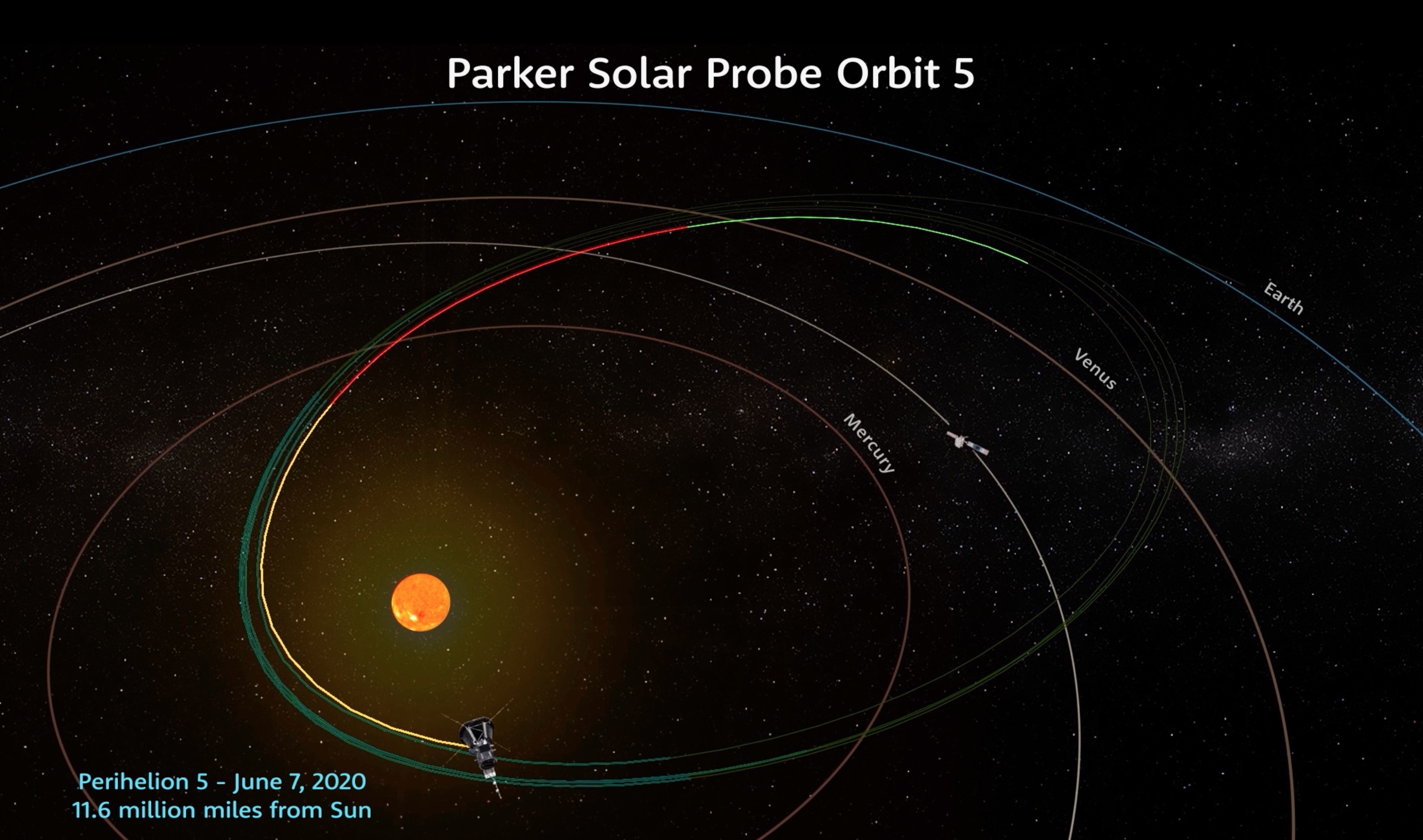

Successful Fifth Solar Encounter

On June 9, Parker Solar Probe signaled the success of its fifth close pass by the Sun, called perihelion, with a radio beacon tone. The spacecraft completed the fifth perihelion two days prior, flying within 11.6 million miles from the Sun's surface and reaching a top speed of about 244,230 miles per hour, slightly faster than the record it set during its fourth orbit on Jan. 29.

Eyes on NEOWISE: Spotting a New Comet

Parker Solar Probe was at the right place at the right time to capture a unique view of comet NEOWISE on July 5. Parker Solar Probe's position in space gave the spacecraft an unmatched view of the comet's twin tails when it was particularly active just after its closest approach to the Sun, called perihelion.

The comet was discovered by NASA's Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or NEOWISE, on March 27. Since then, the comet — officially called comet C/2020 F3 NEOWISE — has been spotted by several NASA spacecraft, including Parker Solar Probe, NASA's Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory, the ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory and astronauts aboard the International Space Station.

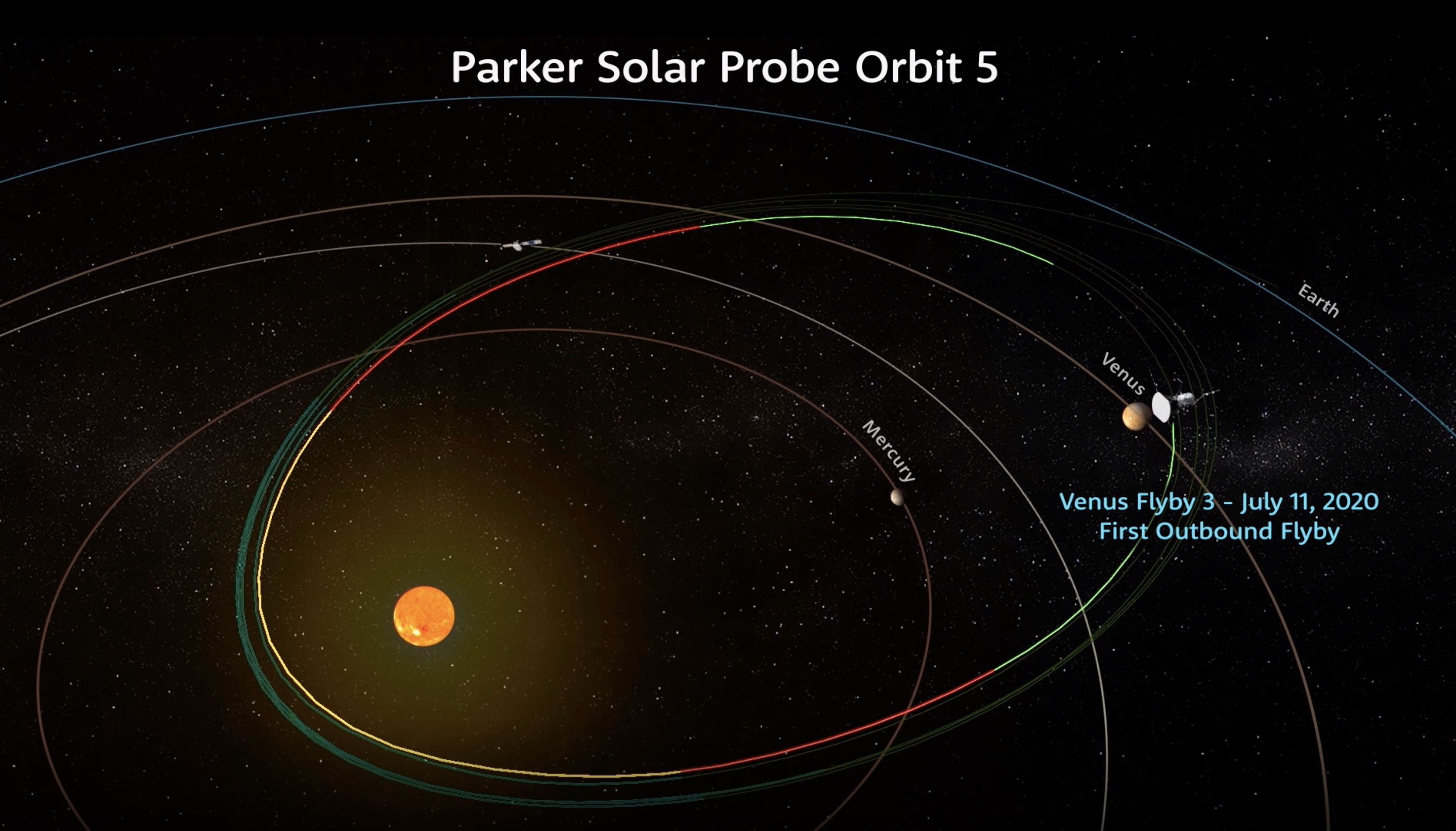

Outbound from Venus

Coming off its fifth encounter with the Sun — and the mission's longest observation campaign yet — Parker Solar Probe headed toward Venus.

Early on July 11, the spacecraft performed its first outbound flyby of Venus, passing 518 miles above the surface as it curved around the planet. Venus gravity assists play an integral role in the mission; the spacecraft "takes" a bit of orbital energy from the planet on each pass, which in turn allows Parker Solar Probe to travel ever closer to the Sun. The mission's previous two Venus flybys sent the spacecraft past the Sun-facing side of the planet; this was Parker Solar Probe's first flight around Venus' night side.

Parker Solar Probe witnessed a brief 11-minute solar eclipse during the maneuver while passing through Venus' shadow. Utilizing powerful telescopes from Earth, the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, Lick Observatory in California and Keck Observatory in Hawaii searched for Venus' aurora while Parker Solar Probe flew around planet. Scientists will combine these ground-based observations with data collected by Parker Solar Probe for unprecedented look at the interactions between Venus and the solar wind.

The flyby set Parker Solar Probe up for its sixth close pass by the Sun, slated for Sept. 27. During this perihelion, Parker Solar Probe will travel even closer to the Sun, setting a record when it passes approximately 8.4 million miles from the solar surface. The spacecraft's seventh perihelion is slated for Jan. 17, 2021.

Media contact: Michael Buckley, 443-567-3145, michael.buckley@jhuapl.edu

The Applied Physics Laboratory, a not-for-profit division of The Johns Hopkins University, meets critical national challenges through the innovative application of science and technology. For more information, visit www.jhuapl.edu.